What athletes can expect from their Big Bay swim, and how to deal with the water temperature… Top tips by tri veteran and Big Bay regular, Frank Smuts.

The Challenge Cape Town triathlon swim will take place in Big Bay, Blouberg Strand – famous for its beautiful view of Table Mountain and chilly blue water.

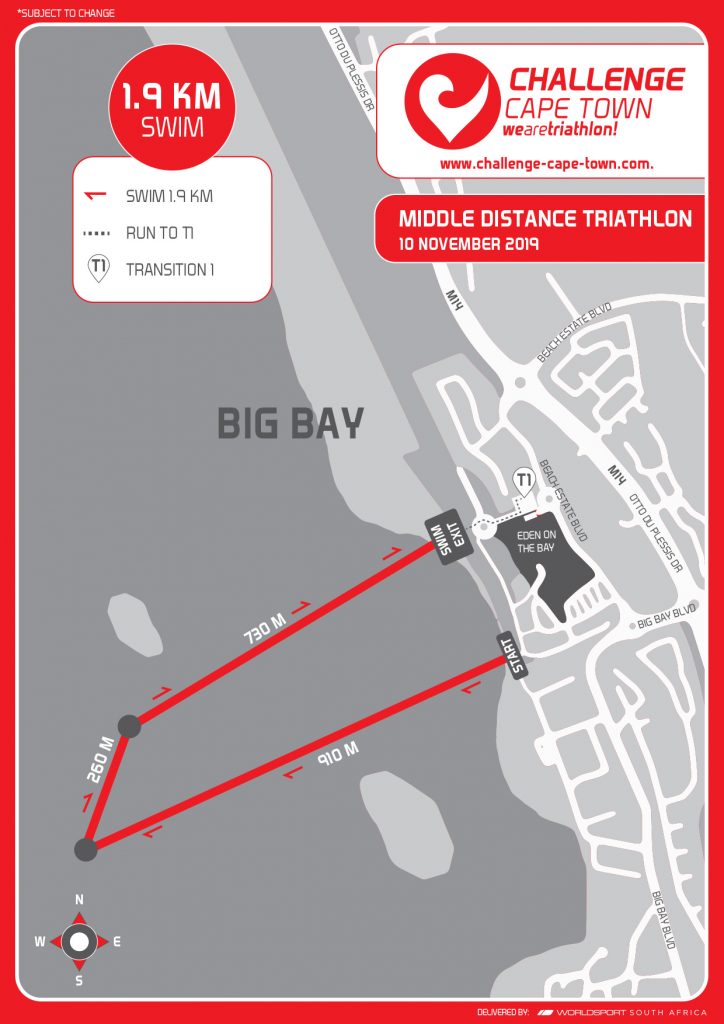

The first leg of the 1,9 km course will take swimmers straight into the sea for 910 m, slightly to the left side of the bay. At the first buoy, with a right shoulder turn, the course goes diagonally for 260 m to the third buoy. After a straight line of 730 m back to the beach, T1 will be waiting.

Dealing with the temperature

The Global Sea Temperature website indicates the average Cape Town sea temperature for November as 17 degrees.

Having done 3 to 6 swims per week in Big Bay for the past 10 years, my trusted Garmin, as well as those of many swim buddies, reflect an average of 15 to 16 degrees.

However, on any given day in November, it can vary significantly from that average, both to the colder, or warmer extremes. There are definite variables at play that can cause overnight temperature variations.

For the record, during a Robben Island swim, we are very happy with 16 degree waters, but 15 is also not scoffed at. Any swimmer in a wetsuit should be able to cope with water down to 15 degrees.

When the temperature goes lower than 15, a real chill might become a reality, but with the proper preparation, even 13 degrees should be no problem. More about that later. Having said that, we have recorded temperatures of 20 to 21 degrees, but those can be counted on one hand, literally.

For race day, 16 degrees should be accepted as a good day. The best case scenario: a very light North Wester three to four days before race day, followed by three or more warm windless days. The North Wester will blow warm offshore surface water into Big Bay, which will be warmed up even more by windless, sunny days afterwards. Under these circumstances 17 degrees or higher is almost a definite. However, North Westers are not very likely that time of the year, but a total absence of wind will also be a perfect scenario. A week of hot, windless days can also result in temperatures of 17 to 18 degrees, or higher.

If the South Easter blows in the days leading up to race day, the temperature will drop significantly. The longer it blows, the colder it gets. The warm surface water gets blown back way offshore and the cold water from the deeper currents goes to the top. Seasoned Big Bay swimmers regard 13 degrees as the “chill point”. That is when cold water can become a factor.

The good news is that a temperature of 13 degrees is totally doable in a wetsuit. As a matter of fact, if you treat it as a PB in terms of what you can handle, it can be a fun challenge.

Just for perspective, English Channel swimmer Howard Warrington (also 7 x Ironman finisher) did a triple Robben Island crossing in 13 degrees, without a wetsuit. That 23 km swim had him in 13 degrees for 9 hours. For race day we’ve got to do 1,9 km in a wetsuit. Nothing can stop us from doing that!

Part of the challenge we are going to embrace with success on race day is swimming comfortably in the beautiful Big Bay waters. What can we do to swim comfortably in cold water?

The obvious suggestion would be to swim in cold water regularly, but what are we dealing with on the way to feeling comfortable in cold water? There are two components at play: the physical and the mental side of cold water swimming.

The physical challenge

On a physical side it can get very technical, but in short, your body will increase its ability to distribute balanced energy to the vital organs and the muscles.

Regular cold water swims will sort that out. The only requirement is persistence. Two regularly spaced swims of 2 kilometers per week are a good minimum. Swimming on a Wednesday and a Saturday would be a good spacing. If you can manage three swims, you will reach superhero status.

Nevertheless, your body will to adapt if you do it right. For example, when you get the familiar “ice-cream head ache”, don’t lift your head, just keep on swimming. Eventually it will become a thing of the past, because your brain will figure out, on a non-cognitive level, how to react to it and direct the blood flow accordingly.

Your metabolic rates eventually adapt to the point that it is almost like a switch that gets flicked when you enter the cold water. Best is to start cold water swims rather sooner than later. In a period of three months everything can be achieved in terms of what you need to deal with cold water.

The mental side of it

The mental side of handling cold water actually precedes the physical side.

Knowing that cold water will not affect you, should be part and parcel of your attitude on race day. The aim is to keep your breathing steady, stay calm and focused, while getting on with the happy task of swimming.

In principle, you should almost be oblivious of the cold, showing no overt, conscious effort to “fight” the cold. But how do we do that? Once again: get used to cold water. As mentioned, two to three sea swims per week will do the job, but it is also about how you do it.

Don’t enter the water on tip toes, acting out trepidation. It only fuels your negative anticipation. Shut out your emotion and get on with it. I remind myself regularly of people who swim ice swims and use them as motivation to “man up” and just swim.

The biggest winning act is to maintain steady, deep breathing. Once you start gasping and disrupt your breathing, you’re nailing the coffin shut. Keep the mental focus to breathe and maintain your stroke as if you’re in a pool.

There are some drills you can do for mental training. Shower drills are quick and convenient. With your next shower, close the hot tap gradually till only the cold water is running. Keep your breathing steady with deep, regular inhales. Get to a point where you can stand relaxed in the cold water for a minute or two. Your resilience and confidence will amaze you soon enough.

When you can do that, step it up a notch with an even more crucial drill. This drill mimics the initial shock of cold water, which derails many unprepared swimmers at the start of the swim leg. When you go for your shower, open the cold water only and deal with it in the same way. Keep your breathing calm and steady. Yoga teachers will tell you: as long as you can breathe steady, you are in control. On race day you’ll be mentally in control and execute a great swim.

Other drills include sitting in ice baths, but personally I reserve my ice for whiskey and injuries. Doing snow angels in a swimming costume apparently also works as a drill, but it does not snow enough in Cape Town.

In the end you might even discover that cold sea swims are very addictive.

When the enjoyment of open sea swims gets hold of you, you will never look back. Every open water sea swim is a fantastic mental journey, as much as it is a physical journey.

The CHALLENGECAPETOWN swim course takes swimmers past the back rocks into the deeper sea, almost a kilometer offshore. If you would look up to your left at the furthest point, you’ll have only the sea between you and Table Mountain. Relish in the prospect of that special moment!

A case for your wetsuit

Let’s look at how a wetsuit affects your swim. For this exercise, I swam 2 km in Big Bay with a Garmin 935 on my arm and inserted a second one inside my wetsuit, right in front of my chest.

The watch on my arm registered 14 degrees and the watch inside my wetsuit registered 18 degrees. The average temperature in a wetsuit is significantly higher than the water temperature.

Knowing that your body has that support is mentally very comforting.

BUT, your wetsuit has to fit well. This means no space for water to flow in. Tighter is always better. Old wetsuits are also a no-no. It might not look perished and fit your contours perfectly fine, but the rubber cells lose their ability to host water in a stable manner. You’ll freeze up without knowing why. I’ve seen many people going from zero to hero when purchasing a new, well-functioning wetsuit. Spoiling race day fitness with inadequate, unreliable gear is not worth it.

If you doubt your suit, get a demo from a respectable brand and do a comparative test swim.

Above: Sea temperature: 14 degrees (Left) and wetsuit temperature: 18 degrees (Right).

About bilateral breathing

Bilateral breathing is a much admired skill, but in cold water, more is better. Get more oxygen, because the demand on your body is higher. Give it all the fuel it can get, so breathe after every second stroke. Bilateral breathing deprives you of a third of all the chances to breathe during your swim. At race pace, it is even more of an unnecessary compromise. Oxygen deprivation has never been anyone’s friend.

Challenge Cape Town will be just that: a challenge. And it starts with the swim. Embrace it. Conquer it. The story you’re going to tell will be worth it.

Happy training!